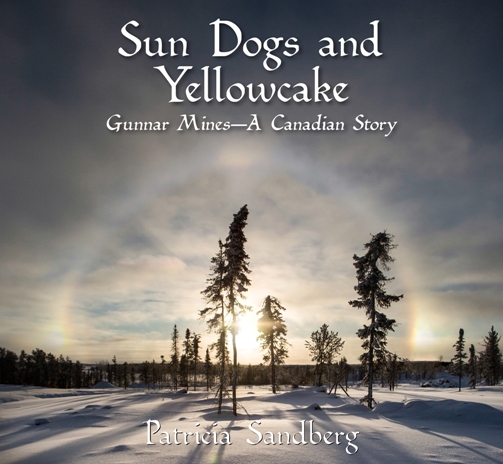

To order a copy of Sun Dogs and Yellowcake: Gunnar Mines – A Canadian Story, click here: http://patriciasandberg.com/purchase-book/

Patricia Sandberg was formerly a partner at DuMoulin Black, a Vancouver law firm acting for mining companies listed on Canadian and international stock exchanges. Her clients had mining operations in Canada, the United States, China, and Latin America. Three generations of her family, including Patricia as a child, lived at Gunnar and her grandfather spent thirty years working at mines run by Gilbert LaBine, Canada’s “Father of Uranium.”

Shooting the Elephant

Re-enter Gilbert LaBine, some twenty years after his radium score and now sixty-two years old. LaBine, in his nominal positions as president and director of Eldorado, was well informed about Eldorado’s moves in the Beaverlodge area. He was also not averse to conducting a little business of his own.

His first foray was with a highly competent, experienced pilot named John “Johnny” Nesbitt, who had spent his life flying in Canada’s north country, including for Eldorado and its Great Bear Lake operations. When Eldorado switched its focus to Lake Athabasca, Nesbitt added the Beaverlodge operation to his flight path.

He had flown the two prospectors St. Louis and Larum to what would later be Eldorado’s Ace mine, and knew the area well. He too had been bitten by the uranium bug and, when not flying, combed the bush looking for his own lucky strike. In 1950, he found and staked a pitchblende prospect on claims that Eldorado had let lapse near Eagle Lake. This prospect would become the Nesbitt-Labine uranium mine.

Johnny Nesbitt wanted to sell the claims to his employer Eldorado; however, he had an unidentified partner who was more interested in a transaction with Gilbert LaBine. Perhaps for LaBine, it was a bit of a poke at the federal government for confiscating Eldorado, and at Eldorado’s president, Bill Bennett, with whom he did not get along.

Whatever the motivation, LaBine promptly resigned from Eldorado’s board of directors to become president of the new Nesbitt-Labine Uranium Mines Limited. Nesbitt did not have much choice but to switch to flying for the new entity. Construction started in 1952 and the small community of Nesbitt-Labine started to grow around the mine.

An interesting game to play

Hopes for the Nesbitt-Labine mine’s success were high but one voice, Johnny Nesbitt’s, expressed concerns that an active promotion was sending the stock higher than it deserved. His concerns turned out to be justified; results were disappointing and the mine closed in 1956.

LaBine meanwhile continued to hunt for uranium. According to the official version of the discovery of the Gunnar orebody, he sent two experienced prospectors, Albert Zeemel and Walter Blair, to the south end of the Crackingstone Peninsula in St. Mary’s Channel, Lake Athabasca. There Zeemel stumbled across an outcrop that he quickly determined was pitchblende and promptly wired LaBine, saying, “I have shot an elephant, I used both barrels,” their code words for a huge strike. It was July 2, 1952 and the new find would be Gunnar Mines. Like many mining deals, it came with a little intrigue.

Nesbitt’s version of the events represents, at the very least, a misunderstanding with LaBine. According to Nesbitt, the two had arranged to jointly explore on behalf of the Nesbitt-Labine company and LaBine’s old Gunnar Gold company. LaBine was to bring in two prospectors for Gunnar while Nesbitt prospected on behalf of Nesbitt-Labine. The two companies would share the costs and any results of exploration, with an agreement reflecting the transaction to follow.

According to Nesbitt, the two prospectors (Zeemel and Blair) had never before seen a Geiger counter. He also contended that LaBine dismissed his suggestion to explore Crackingstone Point. Nesbitt said, “I set them [Zeemel and Blair] right on top of what was to be the Gunnar mine.” He also stated that he wired LaBine to tell him that uranium had been found on St. Mary’s Channel and that when LaBine saw the property, he changed “as day is to night.”

When the promised contract arrived after the finding of the Gunnar ore body, it is not clear what terms it contained, but they did not include any joint deal between the companies. Nesbitt-Labine had been cut out of the deal. Johnny Nesbitt, as an owner of that company, stood to make nothing. Although Nesbitt was upset, he rallied by selling all his shares in other companies and loading up on Gunnar stock which was then trading at 16 cents per share. The true nature of the handshake between Nesbitt and LaBine will never be known. What is certain is that in an aggressive and tumultuous staking frenzy, you had best get your agreement in writing—and in advance.

Albert Zeemel provided a somewhat different background when he recounted his story for the May 1956 Precambrian Journal. Zeemel confirmed that he had no previous experience with uranium, so spent ten days visiting other mines in the district and talking with uranium veteran Emil Walli, the former mine manager at Port Radium, who now fulfilled the same role at Nesbitt-Labine. Walli’s advice to Zeemel: “Always travel slowly and keep your geiger on.”

According to Zeemel, LaBine asked him to do some exploring at Lake Athabasca and said that Blair would accompany him. However, when Zeemel was ready to set out, he was informed that Blair would meet him later in the season but that he would be working for different interests. Zeemel said that he, with a trapper-turned-prospector that Nesbitt had hired, headed off to explore with Johnny Nesbitt in his plane, all believing that, as long as they were together, they would be working on an even basis for Gunnar and Nesbitt-Labine.

They flew in Nesbitt’s Beaver, scouting out likely areas, and staked some claims near Milliken Lake on the Crackingstone Peninsula. Some of these claims were pooled among the group while others were not….

One dump truck plus shovels

“Over on the South Shore (the southern edge of Lake Athabasca), there was a mine called the Murky Fault that had a real high grade of ore. It was owned by a tall, twentysomething fellow. He had a small wooden barge that he had to run a pump on steady so it didn’t sink. He had a big dump truck on board. We towed this barge to the South Shore and pushed it onto the mud so it could sit there without him having to run the pump.

Through the winter, he and a couple of Native fellows shoveled this ore out and loaded it into the dump truck trailer. We pulled the barge back to Bushell Bay and lifted the loaded trailer off the barge, where it was hooked to a truck for transport to the refinery at Eldorado. We then pushed the barge onto the mud so it wouldn’t sink. Shortly thereafter, the young guy paid cash for a brand new Cessna plane.”

—Greg Mockford, crewman on the tug Niangua

END