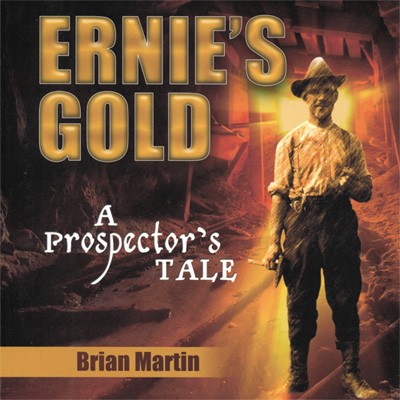

For an autographed copy of Ernie’s Gold, please contact the author at: chipmartin@sympatico.ca .

Great Christmas Gift: $20.00 plus shipping!

In the early 1900s, young Ernie Martin immigrated from Staffordshire, England, to Canada to seek his fortune. He finally ended up in Kirkland Lake, where gold was to be found if you were willing to work at it. Ernie was. And so was Harry Oakes. The two of them became prospecting partners. Ernie and Harry worked hard and non-stop to find a vein of gold so they could start a mine.

When it finally happened, the mine grew into a huge money-maker for the two of them. Ernie’s first wife, Mary, also was a prospector, and in fact ended up financially far better off than Ernie. Why was that? How is it that multi-millionaire Ernie Martin arrived at the end of his life virtually a pauper? This is a book full of surprises and answers — and a few questions.

Excerpt from Ernie’s Gold: A Prospector’s Tale:

By all accounts, Harry Oakes had a comfortable upbringing, not the sort of background that would likely compel him to dream of riches and spend his life pursuing them. Unlike Ernie Martin and so many other men who stepped off the T&NO train at Swastika, Oakes didn’t see finding gold as a means of escaping modest circumstances.

Nevertheless, he was virtually broke when he detrained that June day of 1911. Oakes could have stayed home, avoided deprivation and hunger, the killing cold of winter, the clouds of blackflies in spring, and mosquitoes in summer to enjoy a comfortable life as a doctor.

But Harry Oakes had a fierce inner drive that amazed—and sometimes repelled—those he met. Standing five-foot-six, exactly the same height as Ernie, Oakes was a rugged individual absolutely driven to work until he dropped as he chased his obsession.

He was born on December 23, 1874, in Sangerville, Maine, a farming and lumbering town of about 1,200 in the centre of the state. Because of Harry Oakes and another native son, Hiram Stevens Maxim, Sangerville became known as “the town of two Knights.” Maxim invented the machine gun and, after becoming a British citizen, was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1901. Oakes was bestowed the same honour, largely for his generosity toward a British hospital, by King George VI in 1939, by which time he had become one of the richest men in the British Empire. …

Years later, in 1931, Oakes granted an interview to The Northern Miner in which he described his arrival in the area.

“I came to the North Country from Alaska with hardly enough money in my pocket to buy train fare. I landed in Kirkland Lake June 19, 1911 and pitched my camp on the point where [a mine manager in 1931] now has his house. The district looked good to me right away and I spent many months scouring the area. I had four camps up; one with a little tent and the

other three were just sacks tied together. I was up every morning before daybreak and on the go all day.”

“At night I would make for the nearest of these little camps, cook myself a bite of supper and fall asleep, dog-tired. I worked hard, harder than a lot of these grubstake syndicated prospectors think they have to work today. All that Kirkland country where the big mines are

today had been prospected years before we staked. It is a wonder the veins were not found.

When I was there, most of the prospectors seemed to be afraid of what they called the “red

granite,” but I recognized their red granite as being real porphyry . . . I could never understand those engineers who walked in, turned up their noses and walked out again.”

From his globetrotting, rock-breaking efforts, Oakes knew porphyry was associated with gold deposits, especially in the western united States and Australia. Porphyry is magma that had worked its way into the folds of older granite during later contortions of the rock as the Earth’s crust cooled. It resembles regular granite in appearance but is less regularly crystallized, having been deposited in smaller amounts that cooled relatively quickly. Quartz and feldspar are found in such formations.

In the Kirkland Lake area, a long vein of the late-cooling granitic magma worked its way into a large east-west fissure, or fracture, that became known as the Main Break. In 1911, as Ernie Martin, Harry Oakes, and others picked away at the ubiquitous granite, no one knew the extent of the riches that lay beneath their feet.

Oakes spent his first several months prospecting across a wide area but filed no claims. e more he looked, the more he liked. He saw perfect conditions for gold and concluded that the area bordering Kirkland Lake’s south shore appeared most promising. He found tellurides, telltale greenish grains in the rock, which he had seen in the gold camps of Australia.

Because all prospectors needed supplies, Jimmy Doig’s and Frank Duncan’s stores in Swastika were thriving. At one point, Oakes had a run-in with Doig about unpaid bills and held a grudge for many years, but Oakes got on better with Duncan. At dinner one night, the storekeeper recalled many years later, Oakes announced he had come north to establish a “one-man mine.” Duncan said he replied he had never heard of such a thing, to which Oakes reportedly snorted: “You wait, I’ll show you.” The locals had begun to see the tenacity of the diminutive American.