Canadian Dimension is a Canadian leftist magazine founded in 1963 by Cy Gonick and published out of Winnipeg, Manitoba six times a year.

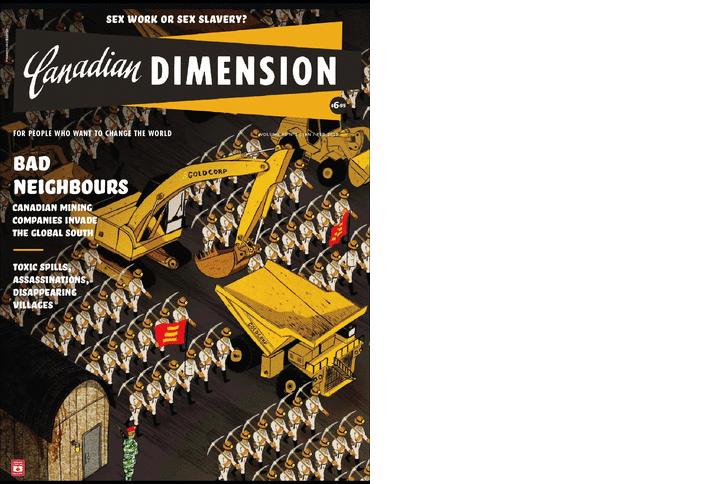

In March 2009, Canada released its long-awaited response to calls for regulatory oversight of the overseas operations of extractive industries such as mining and oil. The Conservative government’s Building the Canadian Advantage: A Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategy for the Canadian International Extractive Sector was drafted in response to years of public, civil society, and parliamentary pressure to remove the impunity with which Canadian extractive companies operate overseas. A 2005 parliamentary report calling on legal reform, and subsequent government-industry-civil society National Roundtables – resulting in recommendations for an independent ombudsman’s office – did little to counter mining industry lobbying and a receptive Conservative government.

The resulting corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy is a tepid response that has no teeth, but we find it a useful starting point to understand just what is CSR and how the world of corporate public relations is appropriating the term for their own benefit.

Nearly every major extractive industry player has adopted voluntary CSR policies or social sustainability statements and a growing body of consultants, socially responsible investors, and NGOs are debating how to promote it. However, ongoing violations of human rights beg the question: is talking in terms of CSR useful to those trying to seek justice for harms committed by Canadian multinationals? Perhaps more importantly, are victims even part of this discourse? Here, we present a deconstruction of corporate and government criticisms leveled at the narrowly defeated Bill C-300, Liberal MP John McKay’s hotly debated Corporate Accountability Act for the extractives sector, and horrible testimonies of injustice at Canadian hands to reveal that we must avoid the snake oil that is the myth of voluntary CSR.

The herculean task of reforming Canada’s extractive sector: simpler than it sounds

The call for reform of Canada’s mining and extractive industry is growing louder. In 2005, after hearing from numerous victims of Canadian companies operating overseas, the bi-partisan Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade released an important report that clearly outlines the necessary steps needed to prevent and respond to such abuses. Recommendations include: legal reform within Canada to hold Canadian corporations liable for overseas operations; to make the Canadian government’s financial and diplomatic support dependent on compliance with agreed upon standards; to improve the oversight and investigative abilities when abuses are alleged; and, to expand services to companies to help improve their performance.

The government’s response to the Standing Committee’s report was to initiate a series of National Roundtables which met through 2006, bringing together bureaucrats, NGOs, industry, academics, international experts, lawyers, and the public. A consensus report emerged from the Roundtables –unprecedented considering the polarized positions held by industry and NGOs – that, while failing to recommend legal reform, called for the creation of an independent ombudsman office to handle complaints, investigate, make rulings, and determine whether companies deserve taxpayer support in Ottawa and diplomatic support from our embassies.

The Conservative government’s response, Building the Canadian Advantage, took two years to prepare and ignores almost every aspect of the recommendations. The government does not set out any binding human-rights norms. Instead of the agreed upon ombudsman office, a CSR “Counsellor” position was created to take complaints but cannot investigate unless the company in question agrees. Worst of all is the absence of the key recommendation that government financial and diplomatic support be dependent on compliance with legal and human-rights norms. MiningWatch Canada, one of the NGOs who participated in the Roundtables, described Canada’s response as a reflection of, “two years of intensive lobbying by industry and the Chamber of Commerce… the provisions of the government’s response are insufficient to assure corporate accountability and protection of human rights and environments.”

However, the fight is far from over. Two private members bills seek parallel though different strategies to fight corporate impunity. The first, Bill C-354, promoted by NDP MP Peter Julian, would see Canada’s civil courts open to international victims of Canadian corporations. Similar to an American bill dating back centuries, this strategy potentially could open up an avenue for victims to seek redress, compensation and other forms of remedy that Canadians take for granted. Bill C-354 is in line with recent efforts by the Toronto law firm Klippensteins Barristers & Solicitors who are pursuing justice on behalf of villagers from Intag, in northwestern Ecuador. Three community members allege that, despite clear warnings, the directors of Copper Mesa Mining Corporation and the TMX Group (who manage the Toronto Stock Exchange) failed to reduce the risk of violent threats and attacks unleashed upon the community after protesting against mining. The community of Intag opposed the company’s large open-pit copper mine and suffered attacks from company security forces as a result. The three Ecuadorian claimants are asking for more than $1.5 billion in damages. In May 2010, an Ontario court struck out the lawsuit though Klippensteins is pursing the case in the Ontario Appeals Court, as the case has the precedent-setting characteristics that could change the face of how justice is pursued by overseas victims of Canadian multinationals.

Bill C-300, Liberal MP John McKay’s effort that was narrowly defeated in Parliament in October 2010, focused not on legal reform but on potential sanctioning of companies found by the Minister of Foreign Affairs to have violated agreed-upon human rights obligations. The Bill would have created mechanisms within the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade to receive complaints and, after an eight-month investigation, make public its findings. Violators would not be eligible for diplomatic support and government financing through the Export Development Bank and the Canadian Pension Plan.

This sanction-based approach is a small step in the right direction and could have complemented legal reforms. Having survived two readings in the House despite full out opposition from the government benches, the Bill failed to make it through third reading due to a decision by a strategic number of Liberal and NDP members to absent themselves from the final vote.

Building the Canadian advantage

The nature of the Conservatives’ opposition to Bill C-300 points to a larger problem haunting CSR. They are successfully framing the debate as a question of protecting our “national interests” and claim dire consequences will follow from anything more than voluntary self-regulation. Missing from this market-based CSR approach is the human cost resulting from such a slow and ineffective “improvement” of corporate behaviour.

Their 2009 response to the Roundtable report is a textbook study in uselessness. The Conservatives created the politically appointed CSR Counsellor position that lacks any authority, is dependent on companies agreeing to be investigated, and has no recourse to sanction companies or demand change. One of the Conservatives’ excuses is that, ‘if we regulate here, won’t the companies be at a competitive disadvantage, and leave?’

Conservative MP Deepak Obhrai argues that “we all know what China is doing … China is all over Africa. Who is asking China to be social corporate responsible? Nobody.”

Obhrai’s response – and the failure of the major press to pick up on its contradictions – lie at the heart of why an industry-controlled and -funded CSR strategy is bound to fail in the pursuit of justice. Such logic, and using it as an excuse to look past the seriousness of the crimes that Canadian companies are implicated in, is disgusting. Unfortunately, this same logic is echoed by another critic of Bill C-300. Carlo Dade, Executive Director of the Ottawa-based Canadian Foundation for the Americas (FOCAL), explained to the Standing Committee that the exit of Canadian-owned Talisman Energy from Sudan in 2003, after the exposure of their ties to the government-sponsored genocide of communities close to the oil fields, was a negative consequence of “activist NGOs.” He went on to say that the Chinese now control the oil, and that Talisman has halted the CSR measures initiated in response to the criticisms. The implication of Mr. Dade’s comment is that it is better to let Canadian companies off the hook for complicity in genocide, rather than having other multinationals commit crimes in their place and reap the profits. Fortunately, the absurd logic was not lost on some of the MPs present.

For the rest of this article, please go to the Canadian Dimension website: http://canadiandimension.com/articles/3613/