Stan Sudol is a Toronto-based communications consultant who writes extensively on mining issues. stan.sudol@republicofmining.com

The Royal Canadian Mint last spring introduced the Victory Anniversary Nickel to commemorate the sacrifices and achievements of our fighting forces in the Second World War. In Sudbury and Port Colborne, Ont., that victory coin has many additional memories, especially for Inco Ltd and its work force.

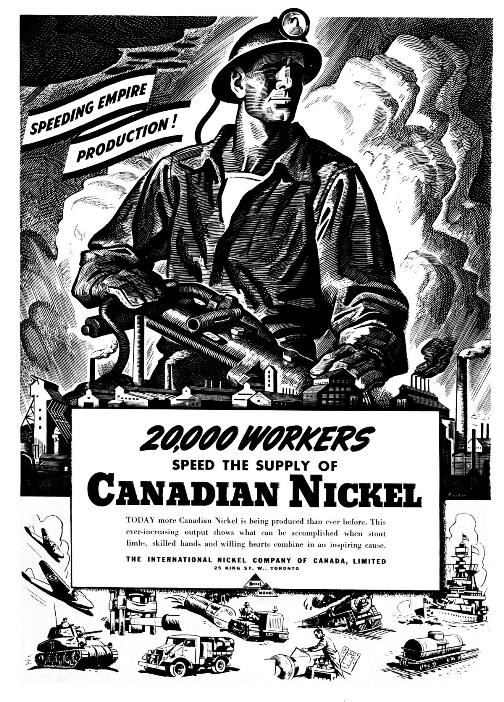

During the war years, International Nickel Company of Canada, as it was known back then, and its employees in Sudbury and Port Colborne, supplied 95% of all Allied demands for nickel — a vital raw material critical for our final victory.

In fact, for much of the past century the leading source of this essential metal was the legendary Sudbury Basin; the South Pacific island of New Caledonia came a distant second. Until the mid-seventies, Sudbury supplied up to 90% of world demand during some periods.

The Basin is an oval-shaped geological structure, 60 kilometres long and 30 km wide, formed when a massive meteorite struck 1.8 billion years ago. These nickel deposits, 400 km north of Toronto, were discovered in 1883 during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Currently, Sudbury supplies about 15% of world nickel production and is still among the top 10 most significant mining districts in the world. International Nickel built the Port Colborne refinery in the Niagara Region in 1918.

Nickel’s unique combination of properties includes strength, hardness, ductility, resistance to corrosion and the ability to maintain strength under high heat. It can transfer these properties to other metals, which makes nickel absolutely essential for a wide variety of both civilian and military purposes.

Today nickel is essential to all facets of industrial manufacturing, primarily through stainless steel, which uses about 65% of global production.

The metal is found in over 300,000 products ranging from heart stents, used in bypass surgery, to hybrid automobile batteries, jet engines and of course the kitchen-sink.

The Second World War was a mechanized war. To win, the Allied armies needed machines — guns, tanks, planes, battleships and a host of other weaponry that could only be made from hardened nickel-steels and other nickel-alloys.

In the mighty flying B-29 Superfortresses, thousands of pounds of nickel alloys were used — in oil cooling units, fastening devices, fuel pump parts, exhaust systems, in instrumentation and tubing and control assemblies for guns, and much more.

The war in the Pacific was an amphibious battle, needing rugged engines with many nickel alloy parts that could withstand the corrosive effects of salt water. Invasion landing craft, submarines and aircraft carriers contained various nickel alloys in the hulls, propeller shafting, gas and water tanks, vital valve and pump parts, gears, firing and other control instrumentation, just to name a few uses.

Armour plate for tanks, anti-aircraft guns and ordnance and even lightweight and tough portable bridges used in the invasion of Germany all required nickel.

From the beginning of the war, International Nickel’s expertise and vast production and research facilities in Sudbury, Port Colborne, Huntington, W. Va. and Britain were fully at the disposal of the Allied war effort.

In 1939, CEO Robert C. Stanley stated, “The first obligation of every corporation, as of every individual, is to give the utmost support to his Government in the prosecution of the war.” As it turned out, these were not empty words. Company profits fell 25% during the war years due to capital expenditures, war taxes and the more costly mining methods to speed up the production of nickel, copper and platinum.

The price of nickel was under government control. From 1939 to 1941 nickel sold for 35 cents a pound. For the rest of the war it was reduced to 31 1/2 a pound. By contrast, the metal cost between 40 cents and 55 cents a pound during the First World War.

Nickel was one of the first metals to require allocation. Non-essential uses of this strategic metal were banned, which included most of International Nickel’s civilian markets. But company scientists and metallurgists worked with former customers to find substitutes.

The 1943 victory nickel coin was no exception. From 1942 until the end of the war, the piece was made from a copper-zinc alloy. In the U.S., the coin contained silver, a much less strategic metal than nickel.

In 1941 the Allied governments asked the company to increase production. International Nickel complied by committing $35-million to expand nickel output by 50 million lbs above 1940 production levels, reaching this goal by 1943 without any government subsidies.

The federal government did, however, allow the company to reduce its tax burden by writing off $25-million in expansion expenditures over a five-year period, instead of 10 or 20 years.

One of the most noted wartime contributions of International Nickel metallurgists in Britain was the invention of a new alloy for jet-propelled aircraft engines.

This alloy, called “Nimonic 80,” allowed the jet engine’s turbine parts, particularly the blades, to work for long stretches under tremendous stress, high heat and corrosive exhaust, without deforming or melting. Nimonic 80 was far superior to its equivalents in German aircraft technology and after the war set the stage for a revolution in jet-propelled aviation.

From the onset of the war, labour shortages caused a constant struggle. Miners were released from the gold camps to work in the nickel operations. Wartime housing shortages in Sudbury probably kept many more gold miners away.

Since 1890, Ontario mining legislation had prohibited the employment of women in mines. Using its powers under the War Measures Act, the federal government issued an order-in-council on Aug. 13, 1942, allowing women to be employed, but only in surface operations. On Sept. 23, 1942, a second order-in-council allowed women into the Port Colborne refinery.

Over 1,400 women were hired for production and maintenance jobs for the duration of the war. They performed a variety of jobs such as operating ore distributors, repairing cell flotation equipment, piloting ore trains and working in the machine shop.

Elizabeth “Lisa” Dumencu, of Lively, Ont., near Sudbury, was 21 at the time and answered the call. “Women didn’t normally do this type of work, but we had to do our part,” she recalls. “It was really remarkable, but my husband, Peter, worked even harder underground.” She ran a 14 ore-car train and became the first woman to work in the machine and blacksmith shop, running a steam hammer. Lisa says “the fellows in the shop treated me beautifully,” but adds that she often looks back on those days and asks herself, “However did I do this?”

Commenting about the role played by women in a 1946 speech, International Nickel vice-president R.L. Beattie said, “Production of nickel and copper in sufficient quantities to assure an Allied victory would have been impossible had the women not stepped into the employment breach early in 1942, when labour was critically short, and the need for our products on the battlefronts steadily increasing.”

At the end of the war, Ottawa rescinded the Order-in-Council allowing the employment of women in the company’s surface operations. International Nickel had a policy to save the positions for all former employees who joined the services, so most of the returning men came back to work for the company.

Nickel consumption fell immediately after the end of the war. However, the rebuilding of the world’s devastated economies and the pent-up civilian requirements for nickel-containing products helped ensure continued demand.

From 1939 to 1945, International Nickel delivered to the Allied countries 1.5 billion lbs of nickel, 1.75 billion lbs of copper and over 1.8 million ounces of platinum metals. The tonnage of ore mined during the war years equalled the production of the company and its predecessors during the previous 54 years of their existence.

On May 17, 1943, a live CBC Radio broadcast from Sudbury announced, “The ships, guns, tanks and planes that today are taking part in a victory which in our hearts, makes us proud and grateful, have been lightened, strengthened or toughened by nickel mined here … and every minute of every day, the nickel produced by the men and women in our audience tonight, toughens and multiplies the sinews of war that will help spell the annihilation of the Axis forces. Here, then, their task is tremendously vital, and their record — a distinguished one.”

When the people of Sudbury and Port Colborne look at that Victory Nickel, they should remember with pride their communities’ wartime contributions that truly helped to shape the course of world history.