Here’s a Graphic Picture of Ontario’s Elliot Lake

A billion-dollar order for uranium

A $300-million spending spree to fill it

A lawless horde of transients

A Communist struggle to control mine workers

A serious outbreak of disease

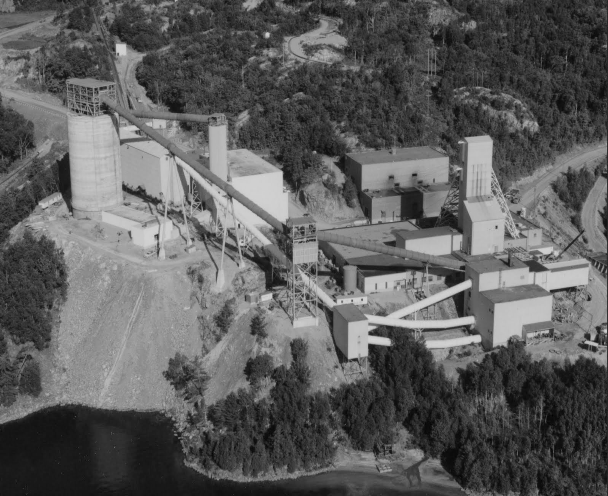

Just off the Trans-Canada Highway skirting Lake Huron’s north shore, a buried vein of ore snakes north through the Algoma Basin in the shape of an upside-down S. It curves for ninety miles beneath the pineclad granite knolls, a mother lode that is spawning eleven giant uranium mines in the greatest eruption of growth since gold gave birth to Dawson City.

The hub of these mines is a chaotic city-to-be called Elliot Lake. Twenty-two months ago it was just a stand of timber dividing two lakes, so wild that a bulldozer leveling brush ran over a large black bear. Today it’s a prime example of a boom town, familiar symbol of dynamic growth – and trouble.

For a couple of months this spring Elliot Lake made headlines that had nothing to do with uranium. An outbreak of jaundice packed ninety victims into nearby Blind River’s 59-bed hospital. About three hundred cases were reported before the disease began to wane early last month. Provincial health officials insisted that the outbreak did not rate as an epidemic while union officials were demanding the mines shut down until the sewage system was improved.

Infectious disease is an age-old bugbear of the boom town, which has its other ageless features. It is the nation in miniature with its time span speeded up as in a silent movie. Here in the backwoods, twenty miles north of the highway, we can see the New World’s vaunted opportunity at its peak. Here, isolated, linked by cause and effect, is the drive for wealth and the struggle for power.

The wealth is “yellow-cake,” semi-refined uranium ore; over the next five years the government-owned Eldorado Mining and Refining Company has guaranteed to buy more than a billion dollars’ worth, enough to make, roughly, fifteen thousand atomic bombs, or the equivalent in energy of five hundred million tons of coal. The struggle is to keep the mines free of Communist control, for a Communist-led union, the Mine, Mil and Smelter Workers, is fighting a bitter battle to win them. The struggle, as always, is aggravated by a complex of social and economic conditions that have little direct connection with politics.

Never before in Canada has so much money been spent so quickly in one place, three hundred million dollars, the bulk of it this year and last. The hills swarm with contractors, blasting roads, sinking shafts, raising mills. The amount of money that powers this boom is incredible, till you grasp the extent of the mines.

Consolidated Denison, on the top stem of the S-curve, is the biggest uranium mine in the world; its ore reserves are twice those of all the uranium mines in the U.S. Even the Pronto, smallest of the eleven, is surpassed elsewhere on this continent only by two mines, one in New Mexico and the other one in Utah.

In their first full year of production, 1958, these Algoma giants will earn a staggering two hundred million dollars. They’ll boost uranium into first place among Canadian metals, ahead of copper, now the number-one money-maker.

“Along this stretch of road,” says Ontario Mines Minister Philip Kelly, “we have greater wealth than Columbus ever dreamed of … we have the world’s great source of a magic mineral with the potential power to change the entire world’s standard of living,”

Four years ago, this area was barren of industry except for the lumber mill at Blind River, a small shabby tourist resort on the CPR and the highway mid-way between Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie. Today a major industry is bursting into life and Algoma is wracked with labour pains.

The first pangs of growth were felt in Blind River, “the hard-luck town” that sank $400,000 in debt when its lumber mill closed during the Depression. Seventy-five companies moved into the area when uranium was uncovered in 1953 by Franc Joubin, an erudite geologist on the payroll of Joe Hirshhorn, a multimillionaire mining magnate now called the Uranium King.

By the following year speculators were dickering with every resident who owned an acre of land. In the back of his restaurant Tom Shamus put up a brokerage board, and customer’s meals grew cold while they watched the latest uranium quotations. Housewives, taxi drivers, even high-school students ran modest savings into five-figure bankrolls.

When the Pronto began production in 1955, the town became a magnet for transients of all types. They jammed the hotels, the beer parlors and the jail. Bootleggers multiplied, rents soared, merchants prospered. The population swelled from 2,400 to 3,200, but even as residents talked last year about reaching 25,000 the boom was shifting centre twenty miles east and twenty north, to Elliot Lake.

Trailers, tents and cabins line the approaches to Elliot Lake. Perched on a hill just above the road is its short main street. The wooden stores have a frontier look. Beyond them, past an empty stretch of uprooted trees, is the residential section: four hundred houses in neat rows, one third occupied, an incongruous fragment of modern suburbia. Nearby are trailer parks and the log bunkhouses of the men who commute by bus to the mines. Nearly three thousand people live in the townsite now and more arrive every day.

They come from the shrinking gold-mining towns of northern Quebec and Ontario, from every province, and almost every country in Europe. They crowd the pool room, the one restaurant, the nightly film show. They’ve given the merchants the jet-propelled start they came to Elliot Lake for.

A sign outside a cabin proclaims; “Elliot Lake Laundry. Established since 1956.” The owners, Mel and Joan Bowman, trucked in equipment a year ago last March. “We worked until two every morning,” Mrs. Bowman says, “but we couldn’t keep even with the business.”

Space is at a premium. Visitors often sleep in their cars. Businessmen bunk in their offices. The Toronto-Dominion Bank operates from a house, the dentist and the hairdresser from a trailer. When the hairdresser’s water line froze just before Christmas, customers lined up outside her door each caring a pail of water.

A modern three-room public school opened with six pupils a year ago January. By the end of the term a new eight-room schoolhouse was needed, and when it was finished in February there were 450 pupils.

The high school is three curtained-off rooms in the recreation hall. The post office is in its third temporary location. Dick West, an engineer with the surveying firm of Marshall, Macklin and Monaghan, says “Every time someone suggests we build something, he adds, ‘Just on a temporary basis of course.’ We have temporary bunkhouses, temporary churches, temporary stores, temporary girl friends. Everything’s temporary. Everything but the mines. And some say they’re Temporary too.”

The pay at the mines is the central fact of life in Elliot Lake. Mine-shaft drillers draw $900 to $1200 a month but these are transient specialist. Mine laborers make thirteen dollars a day, skilled men eighteen, with a daily bonus of five or six dollars for working underground.

“My husband, he’s a machine doctor, he fixes machines,” says Mrs. Margaret Bouchard. “he makes $2.05 an hour. I make seventy-five cents an hours in the laundry. We spend it all. We go to Sudbury or Sault Ste. Marie once a month to shop. Living here is so high.” Why had they left Timmins? “The pay in Timmins – ah, it’s awful!”

In the bachelor dormitories, living is cheaper (two dollars a day). But away from girl friends or families the men grow bored. Some blow their pay in Blind River; one camp cook, while I was there, was giving away five-dollar bills to girls in the Hi-wai Grill; when I saw him last he was filching a quarter tip left for a waitress.

Buses Take to the Bush

Every month a couple of hundred men quit their jobs. The labor turnover is “four to one,” a construction boss told me. He meant he had to hire four men to keep one on the job. A stream of transient labor flows in and out of camp, a continuous source of trouble.

“We’ve got everything here from ex-cons to ruby-dubs,” say Scott Raebould, one of Elliot Lake’s six provincial policemen. “Over Christmas, thefts were fantastic. There’s no lockers for security. Take Denison [mine]. There’s twelve hundred men up there. A hundred may have left that week and somebody’s wallet’s missing. Who is it? You can’t trace them all. We get a message – somebody’s mother’s dead. They want us to locate him. He may be at any one of a dozen mines or construction camps. It may take a whole week to find him. I didn’t get a fishing line in the water once last year. The second day in I had to deliver a baby. You have to be everything here – doctor, psychologist, the works.”

In eleven months last year, twenty-six men were killed building the mines and traffic accidents were numerous. “The road last year was grim,” Raebould says. “A car would drive round a curve and smack into a big trailer unit.” Driving north from the highway there was often no room to pass. More than once the Blind River-Elliot Lake bus took to the bush with a full load of passengers.

Last spring, the road was a river of mud. To drive the twenty miles up from the highway took five hours even by jeep. Some trucks took as long as two days to come in. Jeeps equipped with winches would sling a rope around a tree and winch themselves ahead through the axle-deep mud.

A new road was built last fall but the old one is not forgotten. Drivers swear it was made by a catskinner chasing a jack rabbit. The turns were so sharp, an engineer says that when you saw headlights at night, you couldn’t tell if they came from in front or behind. Two hills were so steep that bulldozers stood by ready to tow cars up. Blind River taxis charged thirty-five dollars to make the forty-mile run and passengers took seasick pills before they started out.

“Every time it rained,” says Don Phillips, a Blind River taxi driver, “you’d see thirty to fifty cars stuck in the mud. When the road iced up you’d see dozens of cars in the ditch … nose first, sideways, upside down.”

Stranded cars, left alone on the road, any road, fall prey to thieves: “I stalled my 1950 Pontiac last July,“ a red-haired plumber named Chapman told me. “I went into town for a tow truck and when I came back it was stripped – brand-new tires, motor, everything. Then they pushed it off the road and burned it. I still haven’t go my insurance.”

One miner broke and axle and when he came back with a tow truck he found his tire gone. When he came back with new tires, his wheels were gone. As many as fifteen stranded cars have been seen at one time on the road – stripped. “They crush in the roof. Break windows. It’s senseless,” Raebould says. “It doesn’t seem to be organized. It seems to be freelance work. We think we’ve pretty well figured out the system. They drive along the road, see a stranded car, drop off a man and drive on. If this guy sees anyone coming he hides in the bush. Then the car comes back and picks him up.”

This ferment is inevitable in a huge construction job so close to road and railway. But it’s aggravated because the mines have trouble holding good miners. There are no houses for rent, seldom a room. A married man must either buy a trailer or pitch a tent or commute back and forth from Blind River, where hotels are usually crammed and families live in converted garages, tarpaper shacks and trailers squeezed into small backyards. “A house, a house, my kingdom for a house,” pleaded an ad in the Blind River Leader.

The mines have a housing program that calls for sixteen hundred houses to be finished by late this year. The mines buy the lots, arrange the mortgage loans with the banks and guarantee the loans jointly with Canada Mortgage and Housing. This gives a miner an $11,265 home for as little as $563 down. But the present programs will only provide a third of thehouses needed and construction lags behind plan. “It’s so slow, it’s pathetic,” says Cy Blackwell, Algom Uranium’s housing officer. “Why? I wish I could answer that question.”

“You just multiply the ordinary construction problems by three, add one hundred percent, and you’ve some idea of what it’s like here,” explains Murray McCrae, a superintendent for Storms Contracting Company, now putting in water and sewers. “There’s everything from solid rock down to silt, muskeg and quicksand. You can be digging dry sand and ten feet away you’ll hit the worst morass you could imagine. This plus the fact that we’ve just had one of the worst construction seasons on record.”

“RED TAPE IS HOLDUP,” headlines the weekly Elliot Lake Standard. Its editor, Ken Romain, says, “The Ontario planning board won’t finance services unless they’re assured that houses are going up and CMHC won’t approve housing loans until they’re assured of services.”

Between Ottawa, ten private firms and the Ontario government, which controls the town until it’s incorporated, construction last year was an often bewildering business. Bell Telephone couldn’t erect poles because the roads weren’t graded. Hydro couldn’t string power lines until the poles were in. Without power, builders couldn’t connect their furnaces and without heat they couldn’t plaster.

Construction is know co-ordinated by a townsite engineer, a globe-trotting Englishman, John Frenneux, who says, “We’re here to see that a city is built as the Ontario government wants it. We’re building in winter in rocky terrain. We’re trying to build it quickly. We’ve got to get more men, more equipment, more contractors.

I asked Ken Skelly, Elliot Lake’s deputy secretary treasurer, what he thought would be the holdup form now on. “Money,” he said. Before CMHC will approve a loan the mines must put up a cash guarantee: thirty-five percent of CMHC’s guarantee. CMHC will not approve loans to private individuals in a one-industry town, not till that industry has been running successfully for twelve months.

“On the one hand,” says editor Ken Romain, “we have [Trade Minister] Howe pushing uranium for all it’s worth, and on the other [Public Works Minister] Winters throwing sand on the fires that Howe is trying to build…Algoma East may have slept undisturbed for fifty years but here are plenty of disturbing issues shaping up now.”

How the Reds Fight for Control

Most disturbing by far, is the prospect of Communist control in these mines, so vital to defense. From their stronghold in Sudbury’s nickel mines, a Communist-led union, the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, are warring with the Soo-based United Steelworkers of America. Algoma in the middle is the battleground.

The dispute between the Steelworkers and the Mine-Mill union has been raging all across Canada since 1949 when the communist-lead Mine-Mill was expelled from its parent bodies, the CIO and the CCI. The Steelworkers challenged the Mine-Mill in three other areas vital to defense in Trail, B.C., which provides heavy water for atomic research; in Uranium City, Saskatchewan and in Bancroft, the eastern Ontario uranium area. Until the Algoma dispute, the Steel union’s only success against Mine-Mill had been in Bancroft, where it now controls the largest mine.

The Algoma battle began in 1955 at the Pronto, the first mine to open. Pronto had signed an agreement with the Canadian Mine Workers Union. Calling this a company union, the Steelworkers sent in Alcide Brunet, a hard-bitten veteran of labor wars. Soon Brunet had signed up a majority of the Pronto’s three hundred miners. Then the steelworkers asked Ontario’s labor board to certify them. The company challenged Ontario’s right to do so. Since uranium came under the Atomic Energy Act, they said, it should be a federal matter. While the pint was being pondered by the Ontario Supreme Court, the board held a vote and the Steelworkers won.

Aided by the pressure of a two-day walkout they wangled what they acclaim as the biggest wage increases in basic industry in Canada – 48 to 78 cents an hour over a three-year period. By July next year, wages at the Pronto and Algom mines will be level with Sudbury, where the pay is the highest of any area in Canada except Trail. Triumphantly, the Steelworkers signed up workers at Denison, the biggest uranium mine in the world.

Then came the Supreme Court ruling: Algoma’s uranium mines came under federal control. This threw the area open. Mine-mill moved into Denison, which, as this is written, they still hold. The Steelworkers hold Pronto and the two Algom mines. Each union is assaulting the other’s position on legal points. It’s anybody’s battle and it’s bitter. On the main street of Blind River last fall, a Mine-Mill organizer, Joe Cominsky, pulled a seven-inch knife on Johnny Beaudry and another Steelworkers official, but police prevented bloodshed.

The front lines are the bunkhouses where daily debates are fought between rival organizers. A victory is signaled by a signature on a union membership card. When a union can count a majority of a company’s men on cards it asks the federal labor board to certify it. If both unions claim a majority, the board orders a vote and this is by no means unlikely in the confusion of Algoma. In one recent month: the Steelworkers Johnny Beaudry, a zealous young organizer, signed up one hundred men. Before the month’s end, sixty-five had quit work.

The organizers are canvassing every miner, one by one in a battle that goes on fourteen hours a day. “They’re tough fighters,” Beaudry charges of the rival union. “Guys will admit that Mine-Mill would take them down to Sudbury and feed them, get them beer, dames, everything you could dream of.”

“We’ve got four full-time organizers,” says Alcide Brunet, once vice-president of a Mine-Mill local in Timmins. “They’ve got eight. They’ve got a bank of organizers in Sudbury, and when the heat is on they bring them all in. They’re fighting for survival. Since they were kicked out of the of the CIO, they’ve lost 278 local unions in Canada and the U.S. They’ve been kicked out of the gold fields. They’ve lost fifty percent of their membership in Canada. We don’t know where they’re getting all their money but we think they’re using Sudbury money for this thing.”

“If Mine-mill can write a better contract at Denison than we have now at Algom,” Beaudry says, “watch out!”

Contributing to unrest in Algoma is what geologist Franc Joubin calls “the five-year phobia” – the belief that when the present five-year government contacts run out in 1962, the mines will fold leaving Elliot Lake a ghost town.

The future of Elliot Lake depends on the market for uranium. The market now is the military stockpile in the U.S. In February, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission reported that present production and the uranium on hand was enough to fill U.S. needs. Military demand seems fairly certain to sag when the present contracts expire.

Will civilian demand take up the slack? The world is on the threshold of a revolution in power – electricity supplied by atomic reactors. Twenty-one are being built or planned in the U.S. Europe is even further advanced. Atomic powered merchant ships and planes are on the drawing board and six more U.S. atomic submarines are under construction. The revolution revealed by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission report has come farther and faster than anyone had realized.

The driving force of this era already upon us is uranium, and the mines that straddle Algoma’s big S seem destined to become the dominant source of fuel in a power-short world. The unanswered question is whether the drive for wealth that created them can solve the social problems of Elliot Lake in time to help the democratic struggle for power.

For other historic mainstream articles about northern Ontario mining, click here:

http://republicofmining.com/historic-articles-about-northern-ontario/